One of the common arguments used to refute the idea that the United States is a Christian nation is the claim that many of the Founding Fathers were Deists. However, this claim is exaggerated.

The overwhelming majority of the Founders were Christians, affiliated with various Protestant denominations, and publicly identified with Christian belief.

A few had Deist leanings, expressing skepticism toward specific doctrines, but only two, Thomas Paine and Ethan Allen, explicitly renounced Christianity in favor of Deism.

Deism is the belief in a creator who does not intervene in human affairs, rejects revealed religion and miracles, and emphasizes reason and natural law over religious doctrine.

Among the Founders commonly associated with Deism or Deist-leaning views were Thomas Jefferson, who rejected the divinity of Jesus and produced a version of the Bible excluding miracles, and Benjamin Franklin, who identified as a Deist in his youth but later acknowledged belief in divine providence and the moral utility of religion.

Thomas Paine, author of The Age of Reason, was a strong and outspoken Deist who rejected Christianity entirely. Ethan Allen, author of Reason the Only Oracle of Man, also openly identified as a Deist.

James Monroe and James Madison are sometimes considered Deist-leaning, though their views were more moderate and private. Madison in particular was known for his strong advocacy of religious liberty and the separation of church and state.

It is important to distinguish these figures from others who are sometimes said to have Deist influences but were more accurately religious moderates or liberal Christians.

George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton all attended Christian services, spoke of divine Providence, and expressed belief in God, though their views were often nuanced and evolved over time.

In total, about four to six prominent Founders demonstrated Deist or Deist-leaning views.

However, the vast majority of the Founding Fathers, particularly the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence and the delegates to the Constitutional Convention, identified as Christians, primarily within Protestant traditions.

Only two were Catholic: Charles Carroll and Daniel Carroll. While some key intellectual leaders held Enlightenment-era views critical of religious institutions, over 90% of the Founders believed in God and identified with a Christian tradition, whether personally devout or culturally aligned.

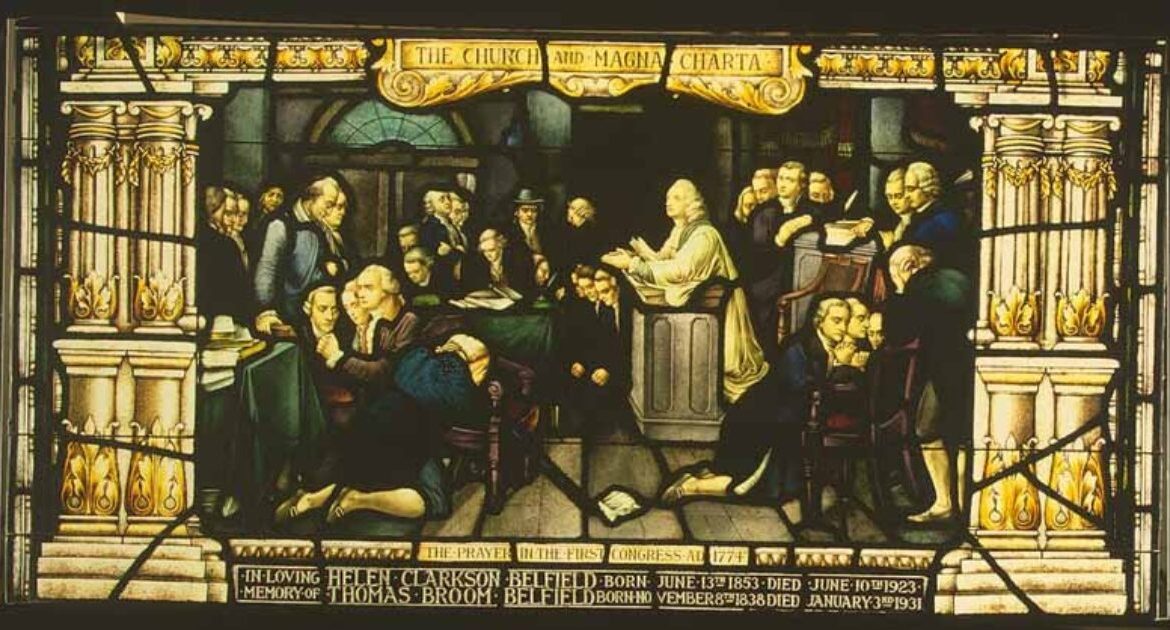

Religious observance was present at several key moments in the founding of the United States. When the First Continental Congress convened in 1774, delegates opened with a formal prayer led by Anglican minister Rev. Jacob Duché and a reading of Psalm 35.

This set the precedent for inviting chaplains to participate in government functions, a tradition that continues in Congress today.

While there is no documented public prayer during the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the document itself invokes “Nature’s God” and “divine Providence,” reflecting the religious language common among the Founders.

At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Benjamin Franklin proposed that the delegates begin each session with prayer, though the motion was never formally adopted.

Nonetheless, in 1789, the same year the First Amendment was ratified, both the House and Senate appointed official chaplains, illustrating the Founders’ belief that religious expression in government could coexist with the prohibition against establishing a national church.

George Washington’s first inauguration on April 30, 1789, also included religious elements.

He took the oath of office with his hand on a Bible and then proceeded with members of Congress to a church service at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City, where Bishop Samuel Provoost offered prayers for the new nation.

These moments demonstrate that while the United States was not founded as a theocracy, religious observance and public acknowledgment of God played a visible role in its early political life.

People often misunderstand the concept of church-state separation, assuming it means the United States is a secular nation devoid of Christian influence.

In reality, the Founding Fathers sought to prevent the kind of religious control over government that had existed in Europe, where both the Catholic Church and the Church of England had wielded political power.

They opposed the idea of any single denomination, Catholic or Protestant, dictating civil law. The Church of England, headed by the British monarch, was especially fresh in their minds as a symbol of religious and political oppression.

What the Founders rejected was state-imposed religion, not Christianity itself.

In fact, almost 100% of the Founding Fathers were Christians by affiliation, primarily Protestant, and many included worship in their public meetings, cited the Bible in their writings, and drew heavily on Christian moral teachings when shaping the nation’s founding principles.

A clear example of the United States’ separation of church and state, alongside its strong Christian heritage, is the fact that the country has no official national religion, as the Constitution explicitly prohibits the establishment of one.

However, it does have a symbolic national house of worship: the Washington National Cathedral, which is distinctly Christian, not Deist or representative of any other faith tradition.

Officially named the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, it is part of the Episcopal Church and located in Washington, D.C. Congress approved its charter in 1893, and President Theodore Roosevelt laid the foundation stone in 1907.

Although it is not a government church, the cathedral has hosted presidential prayer services, state funerals, and national memorials, serving as a ceremonial space that reflects the nation’s historical ties to Christian tradition without violating the constitutional prohibition against establishing a state church.

The post The Founding Fathers Were Overwhelmingly Christian, Not Deist appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.